Haiti had been without a president for a week when, on a Sunday in February 2016, a coalition of politicians and business leaders chose an interim leader to fill the void. The decision temporarily stalled a deepening political crisis in the nation of more than 10 million people.

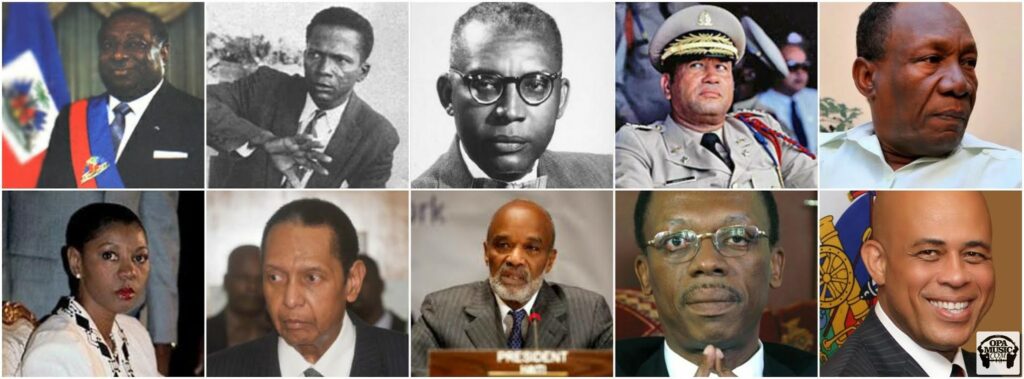

For many Haitians, presidents have not always been a source of stability. Since independence from France in 1804, Haiti has seen 45 leaders, most of whom ruled with heavy hands, enriched themselves, suppressed opposition, violated human rights, and governed with impunity.

“They don’t really want to work for the Haitian people,” said Pierre Espérance, executive director of the National Human Rights Defense Network in Port-au-Prince. “They work for themselves once they get to power. They want to steal money.”

Haiti’s presidency has been equally unforgiving to those who have held the office. Twenty-three leaders have been overthrown, among them Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who was ousted twice. Henri Christophe, who declared himself king in 1807, committed suicide rather than face rebellion. Jean Vilbrun Guillaume Sam was dragged from the French Embassy during a popular uprising in 1915 and brutally killed by a mob. Dictator Sylvain Salnave tried to escape to the Dominican Republic, only to be extradited, court-martialed, and executed on the steps of the National Palace.

There are rare instances of orderly transitions. Michel Martelly completed his term and stepped down peacefully on February 7, 2016, an uncommon occurrence in Haitian politics. But his departure left a vacuum. Elections scheduled to choose his successor were delayed multiple times amid allegations of fraud and growing insecurity.

After days of tense negotiations, Jocelerme Privert, a senator and former head of parliament, was appointed interim president for 120 days. His mandate included organizing fresh elections, though many Haitians remained skeptical. History offered reason for doubt: the last interim government in 2004 took two years to hold new elections.

Whoever assumes the presidency faces daunting challenges. Widespread poverty, entrenched corruption, and broken institutions define the Haitian state. International meddling, particularly by France and the United States, has worsened matters, but many experts insist strong leadership could still set Haiti on a steadier course.

“It requires a leader with a certain strength of character,” said James Dobbins, a senior fellow at the Rand Corporation who has served as a special envoy in Haiti. “Someone able to inspire trust across the social and economic spectrum, someone with charisma and integrity. That combination has not appeared yet.”

Haiti’s first leader, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, set a troubling precedent. After declaring himself emperor, he instituted harsh labor policies, ordered massacres of white Haitians, and was ultimately assassinated under murky circumstances. Since then, instability has often been the rule rather than the exception.

There have been brief flashes of progress. Jean Pierre Boyer unified a divided country but excluded large portions of the population from power, sparking unrest. Fabre Nicolas Geffrard modernized education and infrastructure but misused public funds for personal gain before being overthrown. Lysius Salomon established Haiti’s first postal system and national bank, only to be toppled in a coup.

René Préval, the only Haitian president to complete two full terms, was praised for his honesty but criticized for his inability to unite warring political factions. His efforts underscored the difficulty of governing a nation where leadership has too often been synonymous with corruption or repression.

No family better symbolizes that dark legacy than the Duvaliers. François “Papa Doc” Duvalier ruled with terror from 1957 until his death in 1971, unleashing the Tonton Macoute militia that murdered tens of thousands. He declared himself president for life and treated the treasury as his own. His son, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc,” continued the dynasty until 1986, overseeing a regime marked by political repression, drug trafficking, and grotesque scandals, including the sale of Haitian cadavers to foreign medical institutions. He fled the country amid a popular uprising.

“Thirty years of dictatorship made it difficult to transition to a democratic system,” said Marc Prou, professor of Africana and Caribbean Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

Haiti’s history remains a sobering lesson in the consequences of weak institutions, unchecked power, and leaders who too often place personal enrichment above national progress. Whether future presidents will break that cycle remains an unanswered question.